General considerations for ADC clinical dose optimization

Release time:

2024-05-24 00:00

Source:

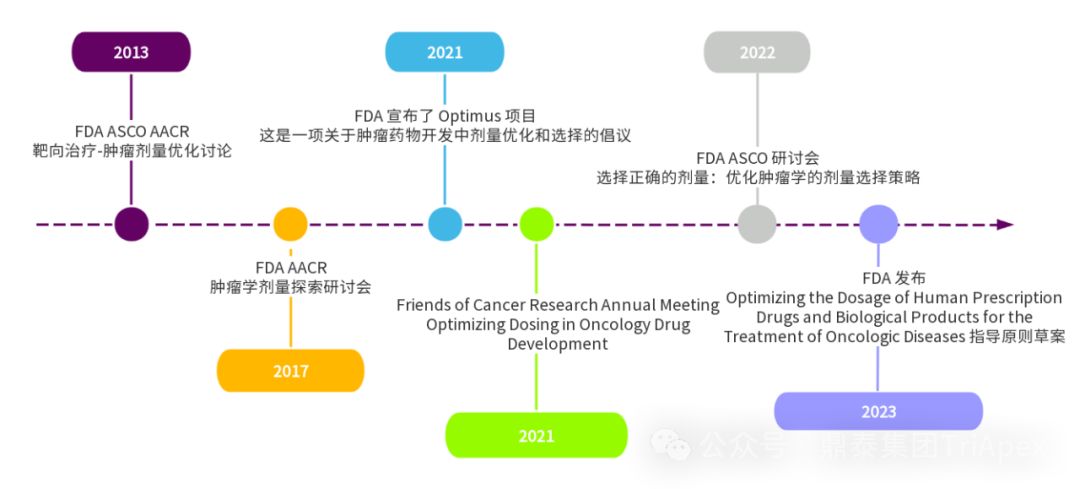

In recent years, dose optimization has become a key focus of the FDA when reviewing new oncology drugs.

Clinical Dose Optimization of Oncology Drugs and the History of Project Optimus

Project Optimus is a project initiated by the FDA Oncology Centre of Excellence (OCE) to reform the dose optimization and dose selection model in oncology drug development. The Project Optimus team is composed of multidisciplinary experts such as medical oncologists, clinical pharmacologists, pharmacologists/toxicologists, statisticians, etc., aiming to work with industry, academia, professional associations, international regulatory agencies and patients to jointly promote this new dose optimization paradigm. Its main goals can be summarized as follows:

-

Education and Communication : Communicate FDA expectations regarding dose finding and dose optimization through guidance, workshops, and other public meetings.

-

Early Interaction : Sponsors are encouraged to discuss dose-finding and dose-optimization strategies with the FDA’s Oncology Division early in the development phase, well before registrational clinical trials are planned.

-

Develop new strategies : Use nonclinical and clinical data to develop new strategies for dose selection that focus on optimizing doses as early and efficiently as possible so that promising new therapies can benefit patients as quickly as possible.

In general, Project Optimus is committed to changing the traditional MTD-based dose selection model and promoting the use of dose optimization strategies to maximize efficacy, safety, and tolerability in oncology drug development.

At present, there are 15 ADC drugs on the market worldwide, of which 7 have entered the domestic market. In clinical practice, the application of ADC is still limited by on-target toxicity, off-target toxicity and other unpredictable adverse reactions. Due to excessive toxicity and unfavorable risk-benefit conditions, many ADC drugs have failed in clinical development. Even for some approved ADCs, many patients need to reduce the dose, delay or stop treatment because they cannot tolerate the related toxicity.

In clinical trials of ADC drugs, it is crucial to determine the FIH starting dose and optimize the dose in subsequent clinical trials. Based on the study and understanding of the FDA's anti-tumor drug dose optimization guide "Optimizing the Dosage of Human Prescription Drugs and Biological Products for the Treatment of Oncologic Diseases Guidance for Industry" and the ADC drug clinical pharmacology study guide "Clinical Pharmacology Considerations for Antibody-Drug Conjugates Guidance for Industry" , the Dingtai team combined relevant literature and cases to discuss the general considerations for starting dose selection and dose optimization in ADC drug clinical trials , in order to deepen the understanding of this issue's theme and provide reference for ADC drug clinical research.

★ Article Guide ★

|

01 |

Related Guiding Principles |

|

02 |

The main toxicities and sources of toxicity of ADC drugs |

|

03 |

Recommendations for clinical dose optimization of ADC drugs |

Related Guiding Principles

1. Guidelines for optimizing the dose of anticancer drugs

In January 2023, the FDA issued the "Optimizing the Dosage of Human Prescription Drugs and Biological Products for the Treatment of Oncologic Diseases Guidance for Industry" [1] , which aims to help applicants determine the optimal dose during clinical development and before submitting applications for new indications and their usage and dosage.

1.1 Limitations of the Traditional MTD Paradigm

Dose exploration trials of anti-tumor drugs (including dose escalation and dose expansion) are often used to determine the MTD. This model is mainly applicable to cytotoxic chemotherapy drugs. Based on the observed steep dose-response relationship and limited target specificity, patients and physicians have a higher willingness to accept toxicity to treat serious, life-threatening diseases. The MTD is determined by gradually increasing the dose in a small number of patients over a short period of time until a pre-defined severe or life-threatening DLT is observed. In subsequent clinical trials, doses at or close to the MTD are usually used without further dose optimization.

1.2 Characteristics of modern targeted therapy drugs

Most modern tumor targeted therapeutics (such as kinase inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies) are designed to interact with tumor-specific signaling pathways. Compared with cytotoxic chemotherapy, targeted therapy exhibits a different dose-response relationship, and doses below the MTD may have similar efficacy to the MTD, but with less toxicity. In addition, the MTD may never be reached in some cases. Patients may receive targeted therapy for a longer period of time, causing lower but persistent toxicity. It is worth noting that in key registration clinical trials, the MTD or the highest dose in a dose-escalation trial is often used. This pattern may lead to poor patient tolerance to the RP2D, adversely affect quality of life, and affect patients' continued medication to obtain maximum clinical benefit. In addition, patients who experience AEs in one treatment may find it difficult to tolerate subsequent treatments, especially in the presence of toxicity superposition.

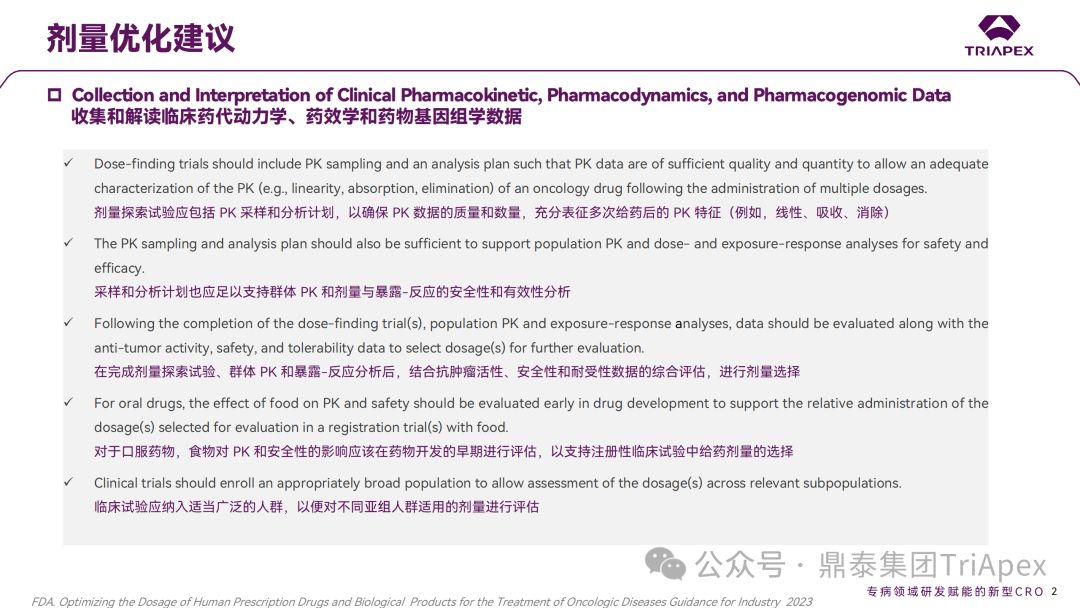

1.3 Recommendations for dose optimization

The traditional MTD paradigm is usually unable to evaluate mild symptomatic toxicity (grade 1-2), dose adjustment, drug activity, dose and exposure-response relationship, and data of specific populations (defined by age, organ damage, concomitant medication or complications). Dose exploration trials can select doses worthy of further study by examining clinical data and dose-exposure response relationships at different doses, which is an effective approach to dose optimization. The following is a summary of the dose optimization recommendations given in the guideline, mainly including:

Collect and interpret clinical pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic and pharmacogenomic data

-

It is recommended that the clinical trial dose be determined based on an evaluation of relevant nonclinical and clinical data

-

Emphasized the importance of collecting and interpreting clinical PK, pharmacodynamic, and pharmacogenomic data

-

Recommendations for inclusion of a PK sampling and analysis plan in dose-finding studies

-

Emphasis on considering dose differences in specific populations in pivotal clinical trials

-

It is recommended to include relevant covariates in ER analysis to assess possible effects on safety and efficacy in different subgroups.

Trial Design Comparing Multiple Doses

-

It is recommended to compare the activity, safety and tolerability of multiple doses in clinical trials to reduce the uncertainty of optimal dose selection during NDA application.

-

A randomized, parallel-dose trial is recommended to compare responses at different doses.

-

Multiple-dose comparison trials are usually completed before registrational clinical trials or conducted in registrational trials by adding an additional cohort.

Safety and tolerability considerations

-

It is recommended to compare the exposure time of different dose groups, the proportion of patients who can complete the planned dose, the percentage of patients who interrupted the dose, reduced the dose and stopped the drug due to AEs, and the percentage of patients who experienced serious AEs (including fatal AEs)

Safety monitoring rules should be pre-defined in the trial design, including doses associated with higher percentages of dose modifications or serious AEs. If the percentage of dose modifications or serious AEs is too high, the protocol should clearly state what actions will be taken, such as pausing the trial to allow a safety monitoring committee to review the events, changing the starting dose for subsequent subjects, and/or stopping the trial.

Certain specific AEs, although they may be mild (e.g., grade 1-2 diarrhea), may seriously affect patients' long-term medication use. The frequency and impact of such reactions (e.g., the frequency leading to discontinuation, suspension, or dose reduction) should be carefully evaluated and considered when selecting doses for subsequent clinical trials.

-

Some anticancer drugs may be associated with early, severe, or life-threatening toxicities that may be alleviated or no longer occur after subsequent dosing. In such cases, the feasibility of using alternative dosing strategies, such as gradually increasing the dose (i.e., titrating) to improve tolerability, may be considered.

-

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) can systematically and quantitatively assess expected symptomatic AEs and their impact on function. In early dose-finding trials, PROs should be considered to enhance the assessment of tolerability. Regarding the selection and frequency of PRO tools, it is recommended to refer to relevant guidelines.

-

When selecting the optimal dose, engaging with patients and other key stakeholders, such as disease-specific patient advocacy groups, can help inform the selection of the optimal dose from a safety and tolerability perspective.

Pharmaceutical preparations

-

Different dosage strengths should be available so that multiple doses can be evaluated in clinical trials. Difficulties in producing samples for multiple dosage strengths are not sufficient reason not to compare multiple doses.

-

For oral administration, the selection of the final dosage form and strength should consider whether the size and number of tablets or capsules required for a single dose are appropriate.

-

For parenteral use, consideration should be given to whether the final concentration and volume are appropriate when selecting the final dosage form and strength.

New indications and dosage

-

Different disease settings or oncological diseases may require different doses based on potential differences in tumor biology, patient populations, treatment settings, and concomitant medications (combination therapy). Applicable nonclinical and clinical data should be considered to support the dose selected in registrational clinical trials and suitability to support subsequent indications and usage.

Before initiating a registration clinical trial, sufficient justification for the dose selected should be provided to support subsequent indications and usage, especially for tumor types or new combination regimens that have not been fully explored in previous dose-finding trials. If sufficient justification for dose selection cannot be provided, additional dose-finding trials should be conducted.

2. ADC Clinical Pharmacology Guidelines

In February 2022, the FDA released the "Clinical Pharmacology Considerations for Antibody-Drug Conjugates Guidance for Industry" [2] , which describes the FDA's current considerations and recommendations on clinical pharmacology in the development of ADC drugs, including bioanalytical methods, dosing strategies, dose-exposure relationship analysis, intrinsic factors, QTc assessment, immunogenicity, and drug-drug interactions (DDIs).

The following focuses on the content related to dosing strategy and dose-exposure relationship analysis, in order to summarize the ideas related to clinical dose optimization of ADC drugs, mainly including:

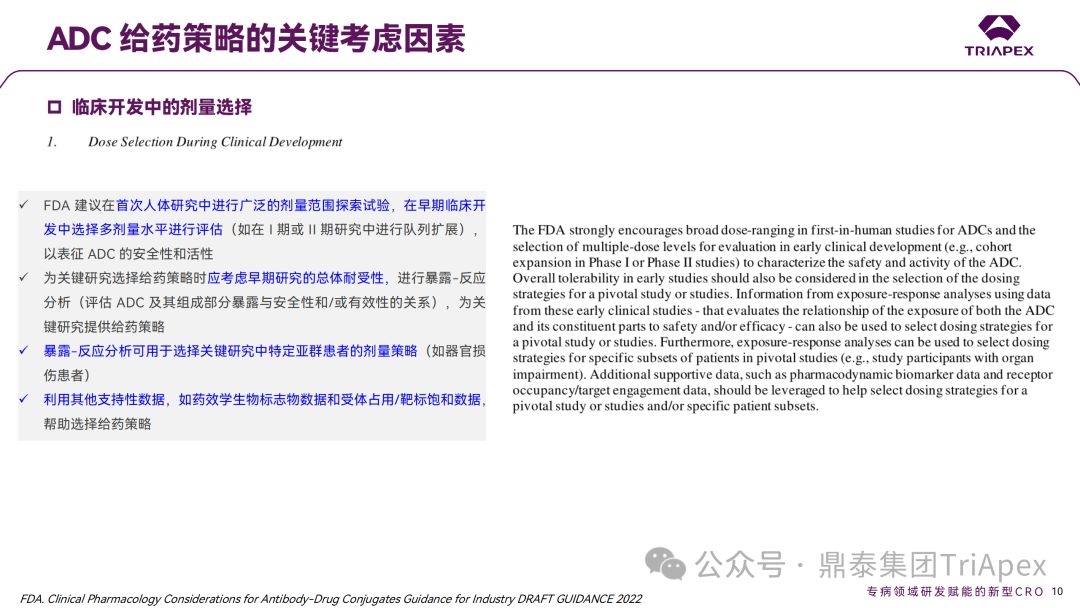

2.1 Dose selection in clinical development

The FDA recommends conducting extensive dose range exploration trials in early drug development, including multiple dose levels and/or dosing regimens (such as single or multiple dosing) to fully characterize the relationship between the ADC and its active ingredient and safety and activity. It is recommended that ER analysis be performed based on the results of early clinical studies to guide the selection of appropriate dose optimization strategies in late development. Fixed doses and weight-based doses should also be considered where appropriate.

2.2 Dosage strategy considerations for intrinsic and extrinsic factors

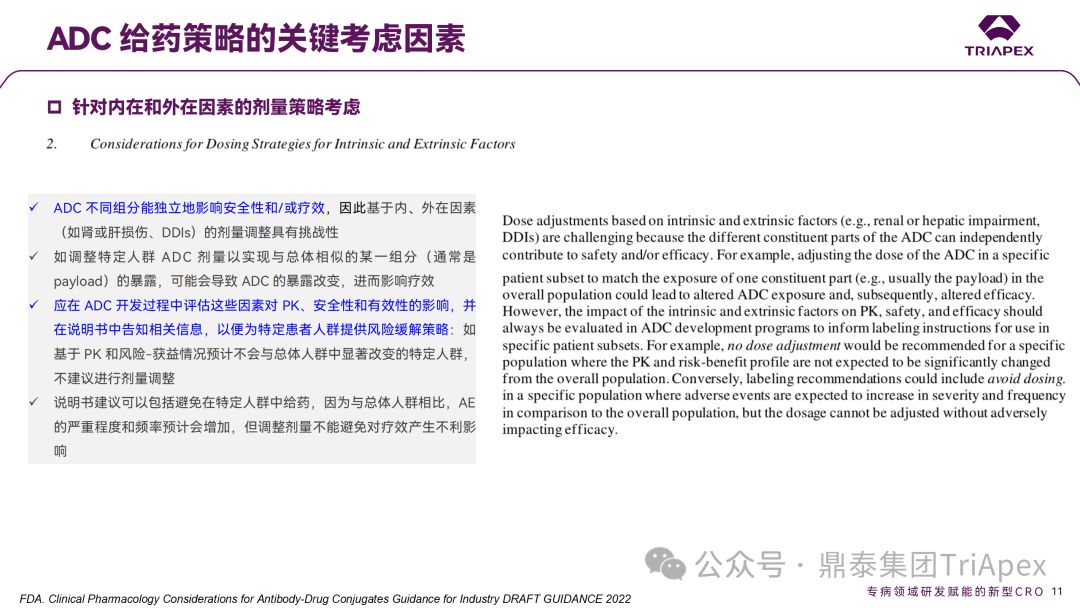

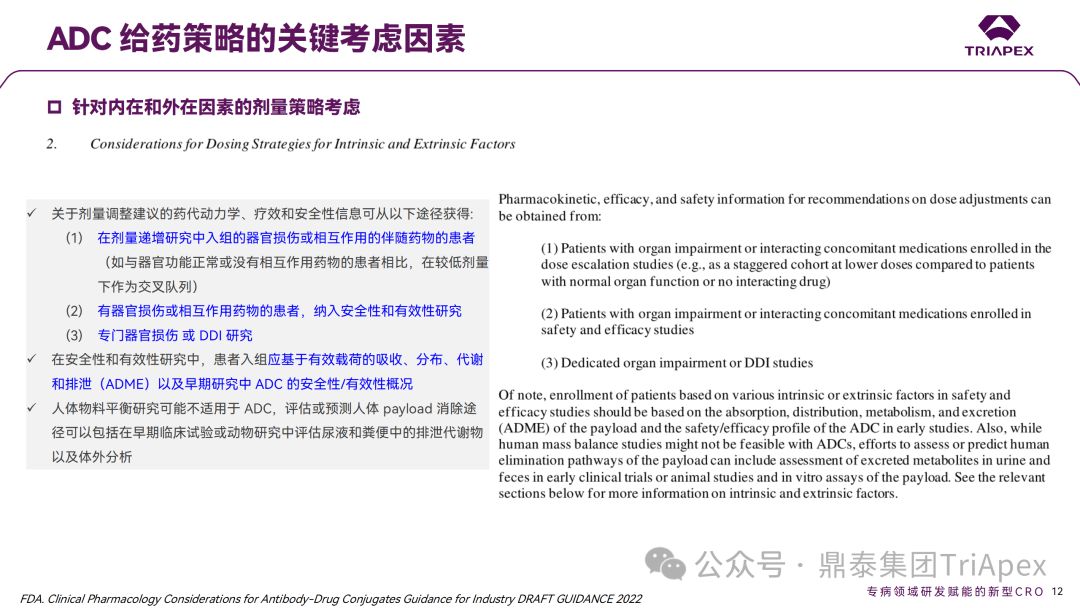

Because different components of an ADC may independently affect safety and/or efficacy, determining recommended doses based on intrinsic (eg, renal or hepatic impairment) and extrinsic factors (eg, drug interactions) is challenging.

Adjusting the ADC dose in a specific population to achieve exposure of a component (usually payload) similar to that of the overall population may result in changes in ADC exposure, which in turn affects efficacy. The impact of these factors on PK, safety, and efficacy should be evaluated during ADC development and the relevant information should be provided in the instructions to provide risk mitigation strategies for specific patient populations.

2.3 Clinical Pharmacology Considerations

All bioanalytical methods should be validated and reported in accordance with FDA guidelines. Starting from FIH, validated analytical methods should be used to detect the concentration of ADC and its components; in late clinical trials, it is recommended to detect ADC and its components and quantifiable pharmacologically active metabolites for ER analysis.

If unconjugated payload is not detected, testing may not be necessary; if the ADC is used only as a carrier and the total antibody concentration is highly correlated with the ADC, testing of total antibody may not be necessary.

2.4 Study-Specific Considerations

In clinical trials of populations with organ dysfunction, it is recommended to measure the levels of ADC, unconjugated payload, and pharmacologically active metabolites. In QTc assessment, usually only unconjugated payload and pharmacologically active metabolites need to be measured. In DDI studies, if the unconjugated payload is detectable, it may be sufficient to measure only the payload; if antibodies may also be involved in DDI, it may also be necessary to measure ADC or total antibody.

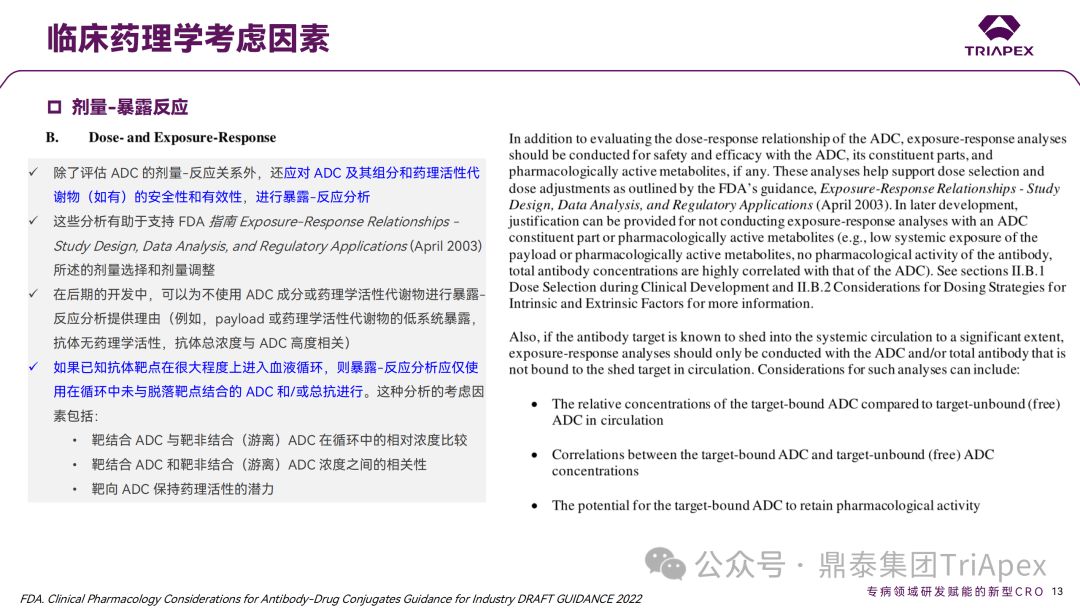

2.5 ER analysis

ER analysis should be performed for both the ADC and its components to support dose selection and adjustment. If systemic exposure of a component of the ADC is low, or the antibody is pharmacologically inactive, or total antibody concentration is highly correlated with the ADC, ER analysis of that component may not be necessary.

The data and analyses from all of the above aspects should be considered comprehensively when making dose selection and strategy considerations.

The main toxicities and sources of toxicity of ADC drugs

1. Main toxicity manifestations of ADC drugs

Based on the instructions, review reports and related literature of ADC drugs approved by the FDA, the Dingtai team summarized the common toxic manifestations of marketed ADC drugs in non-clinical studies and clinical trials. Among them, hematological toxicity is one of the most common and most serious adverse reactions of ADC drugs. Different ADC drugs have different toxicity spectra due to differences in targeted antigens, payloads and coupling methods.

2. The main sources of toxicity of ADC drugs

According to the literature, most ADCs will be uncoupled in non-target tissues after injection, leading to unexpected toxic reactions, and ultimately only about 0.1% of ADCs can be delivered to target cells.

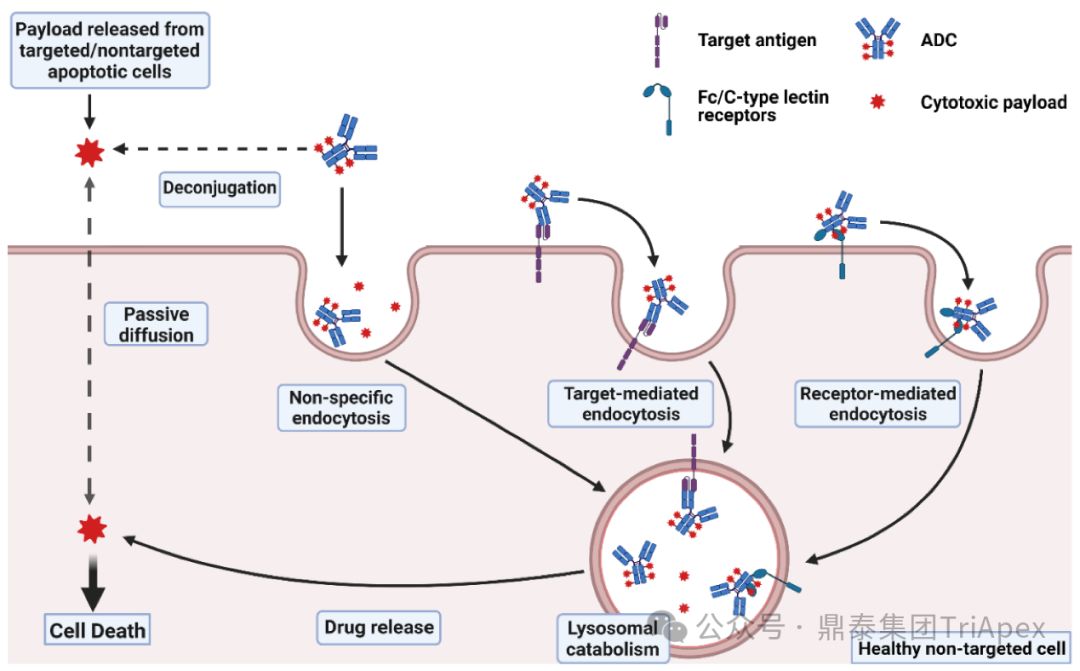

The toxicity of ADC may mainly come from the following mechanisms:

-

Nonspecific uptake of ADC by normal tissues (off-target effects unrelated to target antigen)

-

Tumor-extrinsic target effects caused by antibody binding to antigens in normal tissues

-

Bystander effect caused by cell-permeable payloads

-

Linker stability leads to extracellular uncoupling and off-target toxicity caused by payload release

Therefore, each component of ADC, including antibody, linker, and payload, may have an impact on the safety of ADC.

Mechanisms of ADC toxicity [3]

Recommendations for clinical dose optimization of ADC drugs

1. Design a reasonable FIH starting dose

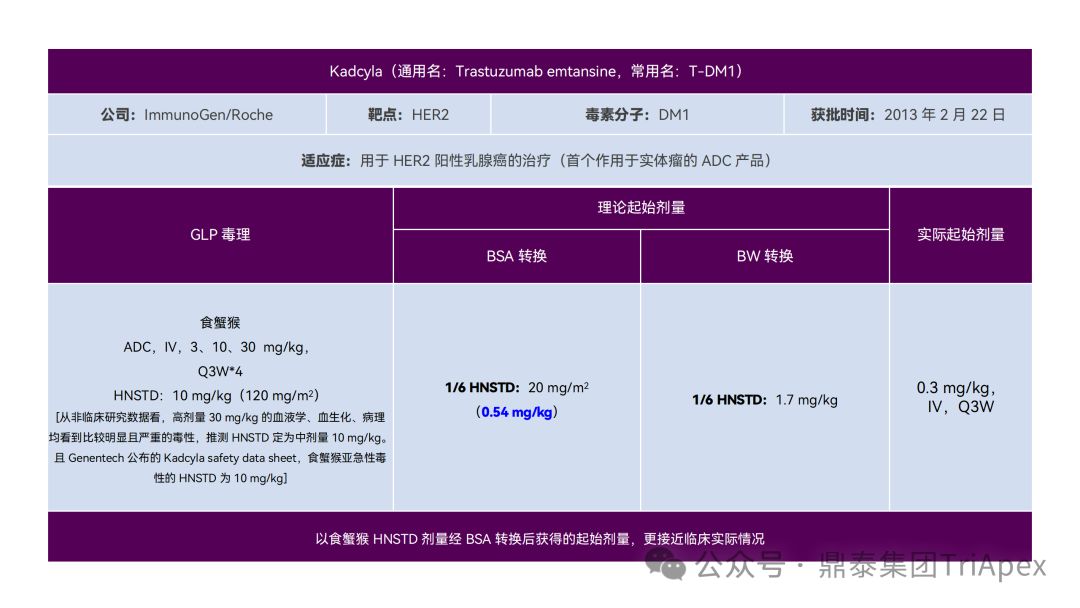

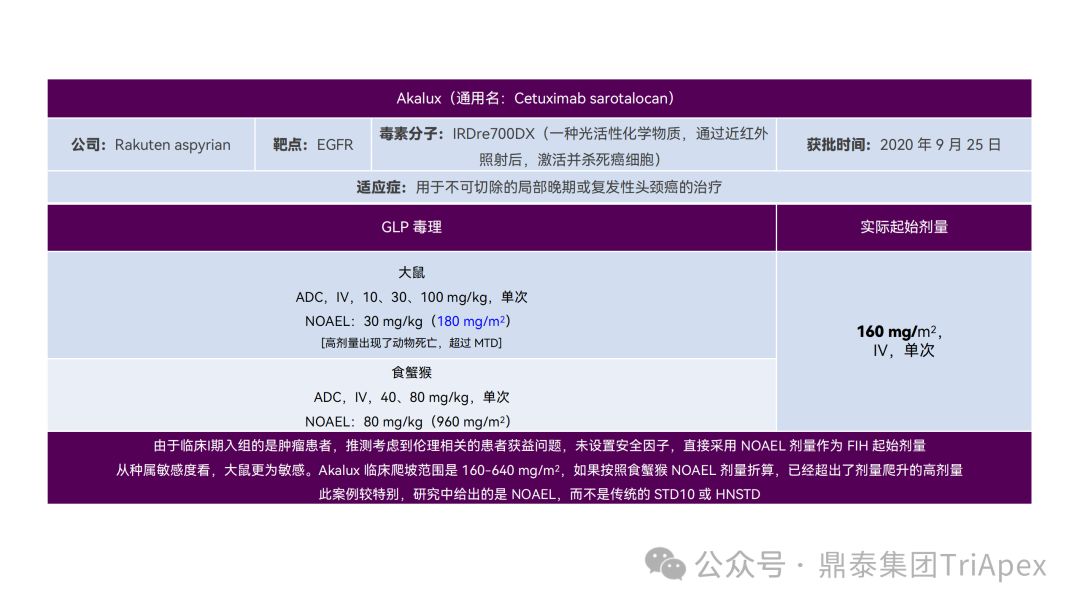

It just so happens that some senior colleagues in the industry have recently deduced the clinical starting dose design of 11 ADC drugs that have been launched on the market. With the consent of the original author, the Dingtai team has further summarized and sorted out the original content (click the link to view the full text) . We would like to thank the original author for his hard work and selfless sharing.

All ADC drugs that have been marketed are for tumor indications. According to the ICH S9 "Nonclinical Evaluation of Anti-tumor Drugs" guidelines issued in 2009, it is recommended to use 1/10 of the rodent STD10 and/or 1/6 of the non-rodent HNSTD as the basis for starting dose design. Based on non-clinical research data, the above guidelines are used to estimate the theoretical starting dose and compare it with the actual FIH starting dose, and reversely deduce the possible starting dose calculation method and possible basis for the marketed ADC drugs.

It is not difficult to find through deduction that the theoretical FIH starting dose calculated by the ICH S9 recommended method for most ADC drugs is not far from the actual dose. From the calculation process, most products have undergone BSA conversion (except Padcev). The reason may be: ADC drugs are highly active and toxic, and the safety window is usually narrow. The use of BSA conversion is more conservative and cautious than BW. This is different from the calculation of the FIH starting dose of monoclonal antibodies or other biological products with better safety.

The above deduction not only helps us better understand the key points of experimental design for non-clinical studies of ADC drugs, but also provides a useful reference for the design of clinical starting doses for new ADC drugs in the future.

Clinical starting dose design and deduction of 11 ADC products on the market

✦

Swipe left and right to view more

✦

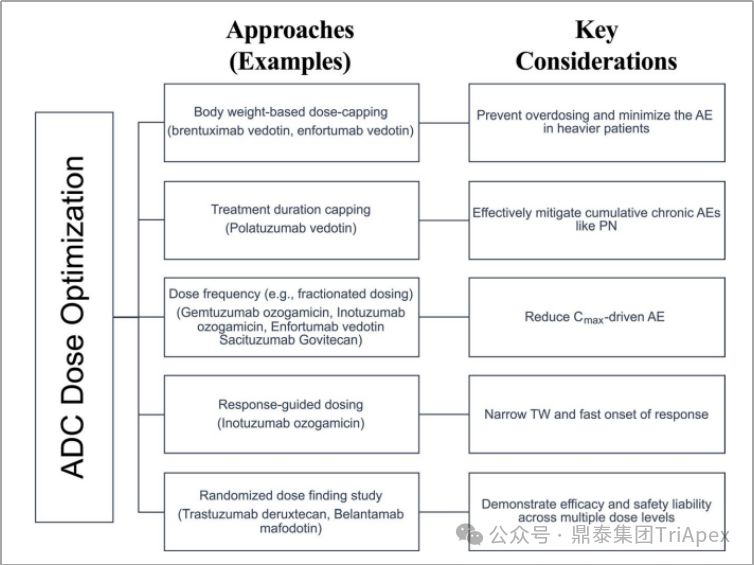

2. Optimize the dosing regimen for subsequent clinical trials

-

Setting a weight-based upper dose limit (such as Adcetris) to prevent overdosing and reduce AEs in critically ill patients

-

Set a treatment period (such as Polivy) to effectively alleviate the occurrence of chronic AEs

-

Optimize dosing frequency (eg, Mylotarg) to reduce C max -driven AEs

-

Adjust the dose according to the patient's condition (such as Besponsa), which is suitable for cases with a narrow therapeutic window and a faster response time

-

and randomized dose-finding studies (such as Enhertu) to elucidate efficacy and safety at different dose levels

ADC dose optimization strategies and key considerations [4]

2.1 Setting an upper dose limit

Adjusting ADC doses according to patient weight can achieve dose consistency while minimizing inter-individual variability and toxicity.

When the power exponent of the effect of body weight on time-independent clearance and volume of distribution is around 0.5, it is recommended to consider weight-based dosing (mg/kg). Generally, when the exponent is <0.5, fixed dosing leads to less PK variability than weight-based dosing; when the exponent is >0.5, weight-based dosing leads to less PK variability than fixed dosing. However, weight-based dosing may also result in higher-than-average exposure in heavier patients.

Cancer patients with underlying diseases such as diabetes and obesity may be more susceptible to AEs. Commonly used anticancer drugs and corticosteroids during treatment may put diabetic patients at risk of hyperglycemia, and dose adjustments may need to be considered to reduce the risk of elevated blood sugar; for obese patients, weight-based dosing can easily lead to over-dose compensation. For example, Adcetris (Brentuximab Vedotin) and Padcev (Enfortumab Vedotin) are both dosed at a BW threshold of 100 kg to reduce inter-individual PK variability and the potential risk of AEs.

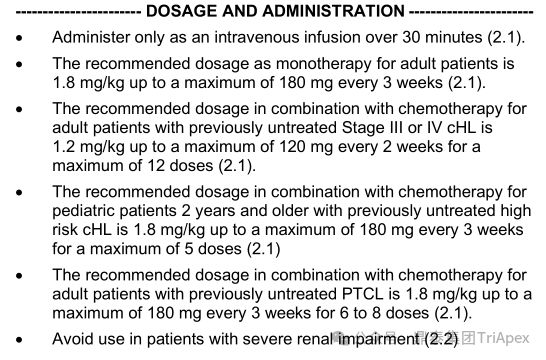

According to the instructions for Adcetris, the dosage of the drug for monotherapy is: 1.8 mg/kg, maximum dose 180 mg, intravenous infusion over 30 minutes, Q3W; for patients with previously untreated stage III or IV classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL), the recommended dose for combined chemotherapy is 1.2 mg/kg, maximum dose 120 mg, Q2W, up to 12 doses. Similar dose caps are also set for high-risk cHL and peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL) patients. In general, the BW cap can improve the safety of ADCs and reduce the variability of exposure levels between individuals. Patients with no weight dose cap who weigh more than 100 kg have an increased incidence of diarrhea and fatigue.

Adcetris recommended dosage, source: FDA Label 2023

2.2 Setting an upper limit on the duration of treatment

Setting an upper limit on the treatment duration can reduce the risk of chronic adverse events during repeated dosing, such as peripheral neuropathy (PN). Studies have found that for a variety of MMAE-containing ADCs, such as Polivy (Polatuzumab Vedotin) and Adcetris (Brentuximab Vedotin), the incidence of ≥ grade 2 PN was related to the conjugate (antibody-conjugated MMAE or conjugated antibody) and was not related to systemic exposure to unconjugated MMAE [4] .

Polivy is a conjugate of Polatuzumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting CD79b, mc-vc-PAB, a cleavable linker, and MMAE. The type of parametric time-to-event (TTE) model predicted that the incidence of ≥ grade 2 PN was 19% and 31% when Polivy was treated at 1.8 mg/kg Q3W for 6 and 8 cycles, respectively, and the incidence was 27% and 41% when treated at 2.4 mg/kg Q3W, respectively. In addition, an independent analysis using 8 MMAE-containing ADCs (approximately 700 patients) found that the risk of PN increased with the exposure level of the conjugate, duration of treatment, body weight, and previously reported PN. It can be seen that adjustments to the dosage and duration of treatment can reduce the risk of PN caused by ADCs containing MMAE.

The above analysis supports the use of Polivy at 1.8 mg/kg Q3W for 6 cycles in patients with relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). Similar dosing regimen optimization strategies may be further applied to delayed/chronic AEs of other ADCs in the future.

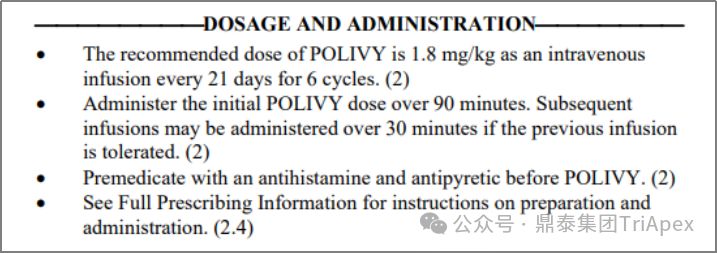

Polivy Dosage and Usage, Source: FDA Label 2023

2.3 Optimizing dosing frequency

Dosing frequency is another important factor affecting the safety of ADC. At the same cumulative dose, optimizing the dosing frequency can reduce C max and improve adverse reactions caused by C max . Adjusting the dosing frequency and treatment interval based on pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) information is essential to maintain efficacy and safety, while also improving patient convenience.

When a single higher dose is divided into multiple lower doses (e.g., 9 mg/kg Q3W is divided into 3 mg/kg QW), each cycle produces the same cumulative dose, similar cumulative AUC, lower Cmax, and higher Ctrough . Therefore, fractionated dosing is expected to expand the therapeutic window by modulating toxicity caused by Cmax and/or efficacy brought by Ctrough .

Fractionated doses can be evenly spaced over the dosing cycle. If target-mediated delivery and/or a strong initial response is desired, a higher loading dose can be followed by a lower maintenance dose, or a dosing interval can be added after the treatment cycle to allow toxicity to subside.

Among the approved ADCs, Mylotarg (Gemtuzumab ozogamicin) best demonstrates the importance of optimizing dosing frequency. Mylotarg, composed of the CD33-targeting monoclonal antibody Gemtuzumab, the cleavable linker AcBut, and the toxin N-Acetyl Calicheamicin, is the first ADC approved in the United States. Initially, Mylotarg was approved in 2000 for accelerated approval for patients with relapsed CD33-positive acute myeloid leukemia (AML) aged 60 years and older who were not suitable for chemotherapy, with a dose of 9 mg/m 2 , IV, Q2W, for a total of 2 doses. In the confirmatory Phase III clinical trial (SWOG 106) after accelerated approval, Mylotarg was used at 6 mg/m 2 (a dose that fully saturates the subject's CD33) in combination with daunorubicin (NDR)/cytarabine (AraC) to treat newly diagnosed AML patients under 60 years of age. The efficacy was not better than standard treatment, and severe liver toxicity and the risk of veno-occlusive disease were found, so the study was terminated. Based on this, Mylotarg was withdrawn from the market in 2010.

In 2017, Mylotarg was re-approved for marketing. A senior colleague in the industry gave an in-depth interpretation of the process (click the link to view the original article) . The following illustrations and notes are quoted from the original article:

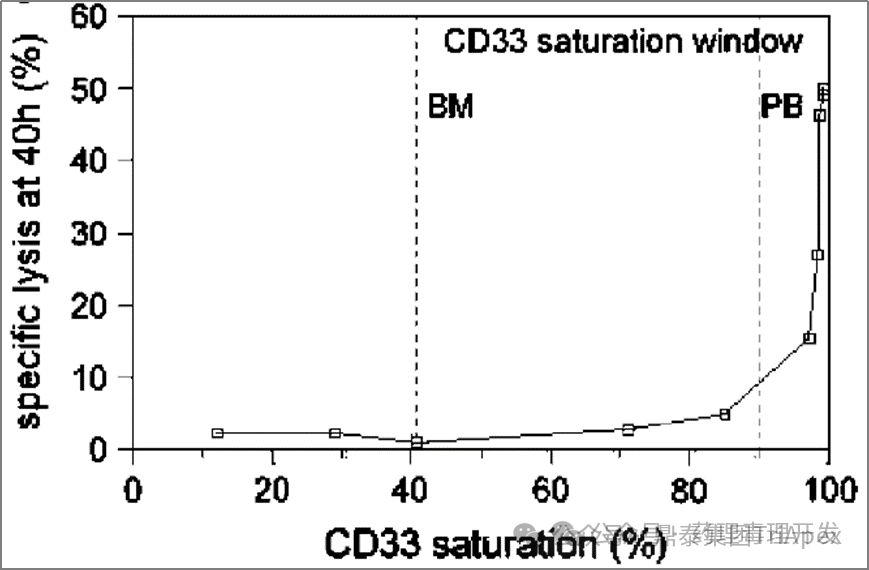

"There is a strong correlation between receptor saturation and drug efficacy. The figure below is also a study using patient PB and BM, and it was found that receptor saturation >90% can ensure the effective killing of GO on cells. When the receptor saturation is <90%, the killing activity of GO is less than 5%. The killing curve is very steep."

"The above research results show that the original 9mg/m2 GO Day1 and Day15 dosing regimen, or 6mg/m2 Day4 dosing regimen, the CD33 receptors in the patient's bone marrow are not saturated, and the killing effect may be very limited. Therefore, a new research idea has emerged, which is to give GO at a higher frequency at a saturated dose, such as giving it again within a short period of time after the first dose, so that the newly generated CD33 antigen can be quickly saturated. In addition, in order not to increase toxicity, considering that more than 90% of the receptors are saturated at 3mg/m2 , the dose can be further reduced. This is equivalent to cutting the original 9mg/m2 , keeping the total dose unchanged, and adjusting it to multiple 3mg/ m2 doses in a short period of time . Based on this optimized trial plan, three proof-of-concept clinical studies have been launched (MyloFrance-1, Acute Leukemia French Association (ALFA)-0701, EORTC/GIMEMA AML-19)."

MyloFrance-1 is an open, single-arm Phase II trial that enrolled patients with CD33-positive AML in their first relapse. Patients received Mylotarg alone at 3 mg/m 2 IV on days 1, 4, and 7 during the induction phase. Patients in CR received cytarabine consolidation therapy. The CR rate in this trial was comparable to the data when the accelerated approval was initially obtained, and the duration of myelosuppression was shorter, with no patients experiencing veno-occlusive AEs. The feasibility of a low-dose, high-frequency dosing regimen was preliminarily verified.

In the subsequent ALFA-0701 trial, Mylotarg was used in a lower or divided dose regimen (3 mg/m 2 , IV, administered on days 1, 4, and 7) in combination with daunorubicin and cytarabine for newly diagnosed AML patients aged 50-70 years. Efficacy results showed that this regimen had a longer median event-free survival (EFS) (15.6 months vs. 9.7 months) and median overall survival (OS) (34 months vs. 19.2 months); in terms of safety, the incidence of thrombocytopenia in the trial group was higher than that in the control group, but the risk of death was not increased. The main reason for the above-mentioned improvement in efficacy and safety is that a lower or more moderate C max and AUC were obtained by administering a lower dose than the initial dosing regimen (9 mg/m 2 , Q2W) . Receptor occupancy tests showed that CD33 saturation could reach over 90% at 2 mg/m2 or higher, while in vivo and in vitro studies showed that CD33 was rapidly re-expressed after Mylotarg administration, suggesting that more frequent dosing of Mylotarg could achieve more sustained CD33 saturation and higher safety.

In another randomized controlled phase III clinical trial (AML-19), patients with untreated AML who were ineligible for chemotherapy were enrolled. During the induction period, patients received Mylotarg monotherapy, IV, at 6 mg/m 2 on the 1st day and 3 mg/m 2 on the 8th day ; the control group received best supportive care. The primary endpoint was OS, which showed a statistically significant benefit (4.9 months vs 3.6 months).

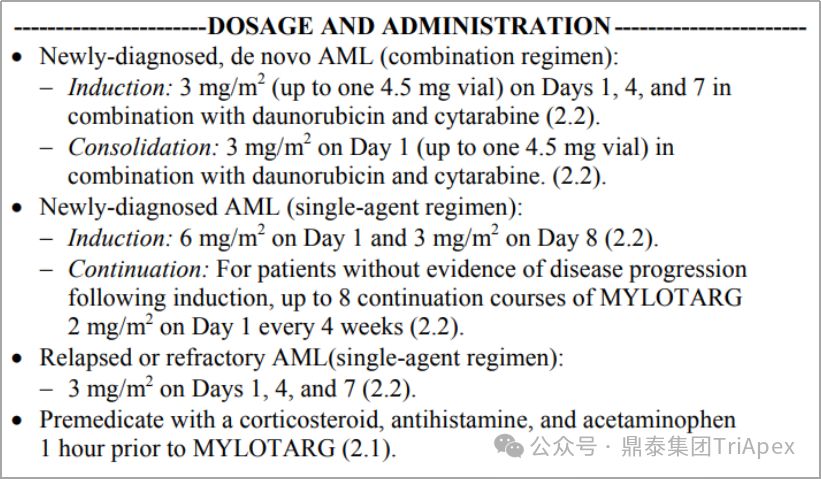

Based on the above clinical trial results, the FDA re-approved Mylotarg (3mg/m2, day 1, 4, 7) combined with daunorubicin and cytarabine for the treatment of newly diagnosed AML in 2017 ; and approved Mylotarg as a single agent for the treatment of adult patients with AML who are newly diagnosed and not suitable for chemotherapy (6mg/m2 , day 1; 3mg/m2 , day 8), as well as relapsed or refractory adult or pediatric (2-17 years old) AML patients (3mg/m2 , day 1, 4, 7). Compared with the 9mg/ m2 Q2W regimen adopted when it was first marketed , the optimized dosing regimen improves the benefit-risk ratio of Mylotarg.

The optimization of Mylotarg dose and obtaining regulatory approval for re-marketing also involves the application of a lot of multidisciplinary knowledge that is worth exploring in depth. A tweet by Professor Zeng Zixiang gave a very detailed and accurate analysis. Click the link for details (PK/PD helps ADC product Gemtuzumab ozogamicin to come back to life - clinical design is a matter of one thought, heaven and hell) . Special thanks to Professor Zeng Zixiang for his summary and guidance.

Mylotarg dosage and usage, source: FDA label 2017

2.4 Adjust dose according to treatment response

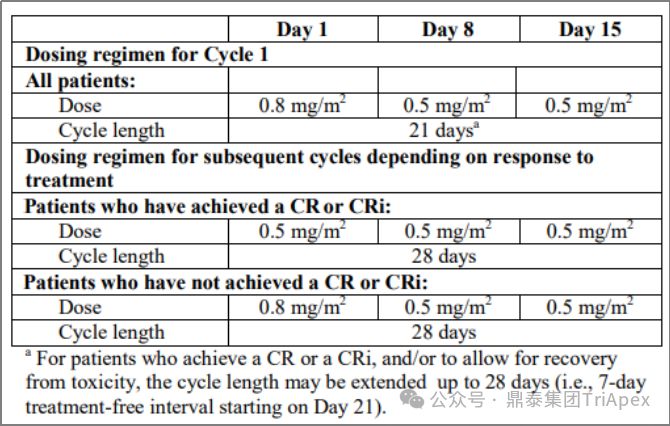

Adjusting the dose according to the patient's treatment response is an adaptive dosing strategy. Besponsa (Inotuzumab ozogamicin) consists of the CD22-targeting monoclonal antibody inotuzumab, the acid-cleavable linker AcBut, and the toxin Calicheamicin. Besponsa uses an adaptive dosing regimen based on early efficacy to address its toxicity (such as thrombocytopenia, venous occlusion) and nonlinear PK driven by treatment response (such as increased exposure in CR/CRi patients). The initial dose of the first cycle (21 days per cycle) is 1.8 mg/m 2 , administered in 3 doses; the dosing regimen of subsequent cycles is adjusted according to the response:

-

If the patient achieves CR or incomplete count recovery (CRi), the dose is adjusted to 1.5 mg/m 2 per cycle (28 days as a cycle) , still divided into 3 doses

-

If CR/CRi is not achieved, resume to 1.8 mg/m 2 per cycle (28 days per cycle)

Besponsa dosage and usage, source: FDA label 2017

The rationale for dose reduction was to help reduce toxicity, as higher Besponsa exposure was observed in CR/CRi patients, suggesting that tumor burden or cell counts may affect Besponsa elimination (i.e., response-dependent PK). In clinical trials, dose adjustments were very common late in the treatment cycle, with the majority of patients experiencing AEs after 1.8 mg/m2 per cycle , leading to dosing delays (78%) or dose reductions (22%).

2.5 Randomized dose-finding study

Phase II/III clinical trials usually do not provide efficacy and safety data at multiple dose levels, which is a major obstacle to dose optimization in oncology and immuno-oncology. Ideally, prospective studies using multiple randomized dose levels and a sufficiently large sample size can maximize the understanding of the benefit-risk profiles of multiple effective dose levels and their ER relationships, which will provide critical support for dose selection and optimization.

Two FDA-approved ADCs, Enhertu (Trastuzumab deruxtecan) and Blenrep (Belantamab mafodotin), adopted this strategy in phase II clinical trials.

To determine the recommended dose of Enhertu in HER2-positive, unresectable or metastatic breast cancer, patients were randomized 1:1 to receive 5.4 mg/kg or 6.4 mg/kg in a Phase II clinical trial. The ORRs of the two dose groups were 52.6% (20/38) and 55.7% (34/61), respectively, and the model-predicted 6-month PFS rates were 87% and 90%, respectively. Overall, the 6.4 mg/kg dose is expected to have better efficacy, but it also increases the risk of TEAEs or discontinuation/dose reduction due to TEAEs. Based on the benefit-risk profile predicted by the ER relationship and PK analysis, 5.4 mg/kg Q3W was selected as the recommended dose.

Dingtai Group has focused on the non-clinical evaluation and clinical research of ADC drugs for many years, and has accumulated research experience in nearly 50 ADC drugs, laying a solid foundation for our partners to quickly advance their ADC drugs to determine PCC and enter clinical trials.

The targets involved in these products include popular targets such as HER2, Trop-2, DLL3, CLDN18.2, EGFR, FRα, B7-H3, EGFR/TAA, as well as mainstream toxin molecules such as SN-38, Dxd, Exatecan , MMAE and Eribulin.

Dingtai Group always adheres to the premise of science and the guidance of drug policy, providing integrated and in-depth empowerment for ADC drugs from molecular discovery, non-clinical research (supporting IND and NDA), clinical development (early clinical, dose optimization, key clinical) and registration declaration.

Dingtai Zhigaodian - ADC Hot Articles & Typical Project Cases

The dose optimization diagram breaks the wall, and the divided dose administration is creative.

Translational research is bold and modeling and simulation are well-founded.

Teacher Zengzi has ideas, and they complement each other's true friendship.

Benefits and risks are interdependent, and clinical value is established.

References:

[1] FDA.Optimizing the Dosage of Human Prescription Drugs and Biological Products for the Treatment of Oncologic Diseases Guidance for Industry

[2] FDA.Clinical Pharmacology Considerations for Antibody-Drug Conjugates Guidance for Industry

[3] Nguyen, T.D.; Bordeau, B.M.; Balthasar, J.P. Mechanisms of ADC Toxicity and Strategies to Increase ADC Tolerability. Cancers 2023, 15, 713. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15030713

[4] Liao MZ, Lu D, Kågedal M, Miles D, Samineni D, Liu SN, Li C. Model-Informed Therapeutic Dose Optimization Strategies for Antibody-Drug Conjugates in Oncology: What Can We Learn From US Food and Drug Administration-Approved Antibody-Drug Conjugates? Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2021 Nov;110(5):1216-1230. doi: 10.1002/cpt.2278. Epub 2021 Jul 8. PMID: 33899934; PMCID: PMC8596428.

Disclaimer: This article comes from the content team of Dingtai Group. Individuals are welcome to forward it to their friends circle. Media or institutions are not allowed to reprint it to other platforms in any form without authorization. If you need to reprint it, please add WeChat LXL--7. This article is only for information exchange and not for commercial profit. The content is only for sharing and learning.